While I love animals in general, I’ve always been most passionate about all creatures feline. For the last 20 years or so, my husband and I have always had three rescued cats at any given time. When one cat passes away, we rescue another from a shelter or the street. When I can remember, I fill a bird feeder in our backyard for my own enjoyment, but also for our cats’ entertainment.

One afternoon a couple of months ago, I noticed a lone pigeon among the groups of quails, doves, and cactus wren who eat at our feeder. I thought to myself, “that’s odd; I’ve not seen a pigeon in our area of Scottsdale before.” The pigeon looked like the kind we’d see in the streets of NYC, but more robust with glossier feathers. I forgot about him and went about my business. When he showed up over two consecutive days, my curiosity increased. I went out to get a better look and noticed a green band around his little leg. That piqued my interest! I did an Internet search of “pigeon green band leg” and all of this information about the sport of racing pigeons cropped up. I’d never even heard of such a thing. Well, I educated myself quickly, learning that it was somewhat controversial among animal welfare groups, but that the people who engaged in the sport purported to fancy pigeons as well. We continued to feed the bird (who we named “Woot” because of the noise he’d make when we approached him) and established a routine. Like clockwork he would show up between 2 and 3pm for his little dish of food and to take a drink from our pool.

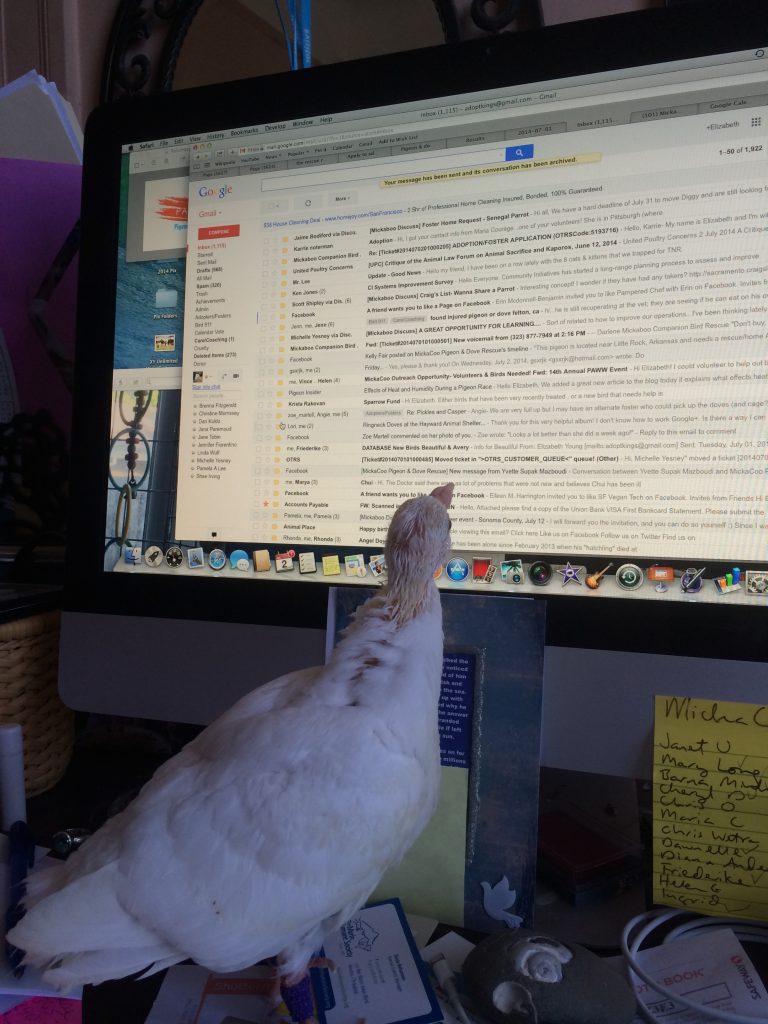

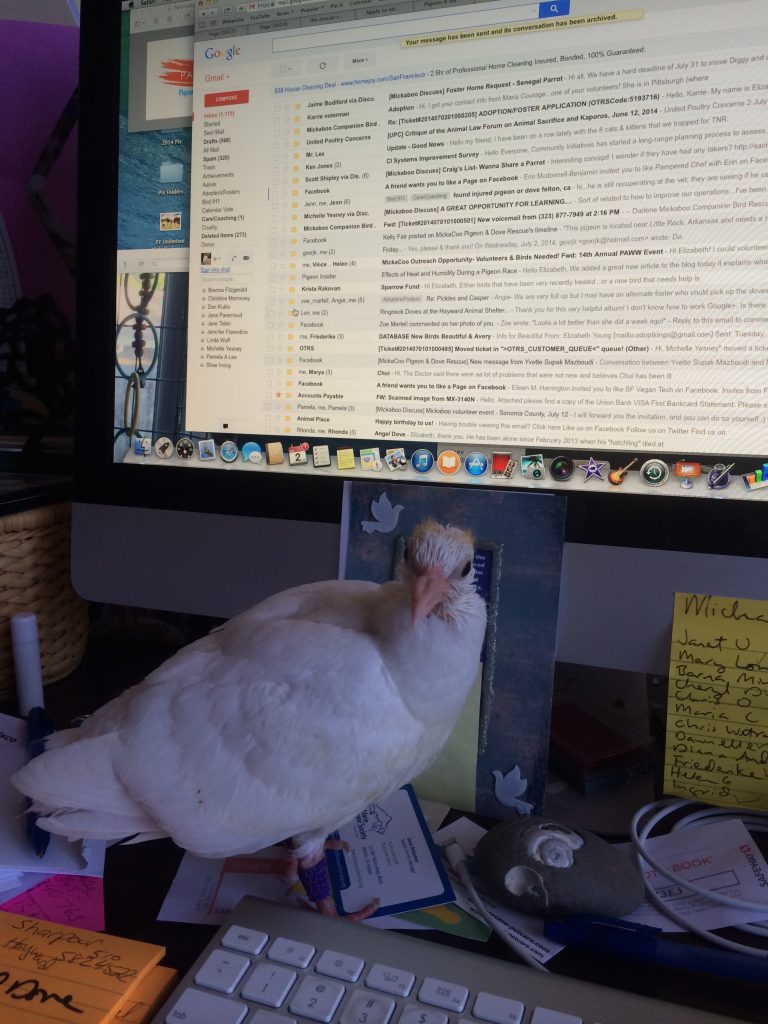

When we went on vacation we asked our cat sitter to feed him outdoors and she told us that when he saw her through the glass he’d peck at it to get her attention. Eventually my husband was able to get close enough to Woot to write down the numbers that appeared on the leg band. Those numbers led me to a contact person at the local pigeon racing club who in turn provided me with the name and phone number of the owner. The owner told me that Woot didn’t come back after his race six months ago, although his sister did. We speculated that Woot had an injured wing, because his flying had declined over the last couple of days. I realized that I didn’t want to give Woot back. If he wasn’t a good racer, and had an injured wing, what kind of life would he have at the loft? Also, to be honest, he touched my heart with his intelligence and vulnerability. With not a small amount of trepidation about what we’d be getting into, I asked the owner if we could keep Woot. He agreed. My husband captured him and put him in our cat carrier. As we knew nothing about pigeons, I relied heavily on Elizabeth at MickaCoo Pigeon & Dove Rescue and the people in Arizona she put me in touch with. One woman recommended a vet not far from where I work, so thinking Woot might have a broken wing I took him for a check- up while my husband scrambled to find a more suitable housing space. Other than a few lice, Woot checked out fine at the vet and moved into a 2’ X 2’ X 3′ hutch my husband found on Craigslist. We knew this would not be enough space for a healthy racing pigeon in the long term. For us, having him inside with the cats while we worked all day didn’t make sense either. So I learned from MickaCoo that the other option was an aviary.

Well, how can I explain what happened next? I’m not fully clear on it myself. It’s sort of like making a leap of faith, or taking a plunge and making a commitment. One suppresses the trepidation and goes for the greater good. Woot really inspired us. An out of place pigeon, selectively bred for a sport he didn’t choose, trying to survive on his own…we decided to help him and that it would be both cool and joyous to have an outdoor aviary. We decided to build it. Fortunately, one of us is very handy (not me) and was up for the challenge. We studied the plans on the links provided by MickaCoo, as well as on other sites. We spent every day of the long Labor Day weekend making trips to Home Depot and creating the aviary. We actually enjoyed the project…a shared experience, something both challenging and productive. For Woot, after spending one week in the smaller hutch, he had a new 8’ X 4′ X 8’ home. We are bonding with him a bit more every day, and after allowing him further adjustment time, we plan to get a female companion pigeon. We will use wooden eggs as birth control, because we are not interested in breeding pigeons. Now, after a lifetime of admiring felines, I’ve apparently broadened my fancy to pigeons. I’m immensely grateful to Elizabeth and her colleagues for their amazing support and advocacy for these beautiful birds.

Clever self-rescuer Woot has inspired his family to adopt another pigeon too. To be continued…

Editor’s note: Pigeon racing kills pigeons. Every year, thousand of pigeons are bred for racing. They are taken hundreds of miles from home and tossed (as it’s called) to their fate. All will try to fly home but only a fraction will survive. They are not racing- they are just trying to get back to their family and home. Woot is extremely lucky. You can learn more about pigeon racing here.