Reprinted from no mushrooms

Bird Lady on line one

It was a spring evening four years ago and the grim reality of COVID and life under lockdown was fully sinking in. As were the effects of a double martini, which pretty much explains how we came to think that constructing a small aviary from scratch in the backyard — and adopting the three pigeons at the Berkeley shelter — was not only a well-intentioned idea, but a practical one.

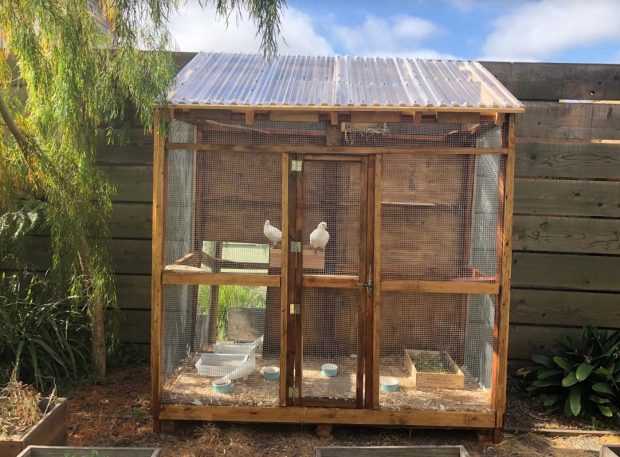

As little as I knew about caring for feathered creatures, I knew less about creating a structure to house them. The truth is, Mike did 100% of the design of the thing and 75% of the building it. I was just grateful to be entrusted with the circular saw once in a while (and to receive sage advice like closed-toed shoes might be a good bet here). As with any legitimate construction project, it took longer than expected to complete, but by mid-summer it was ready for tenancy.

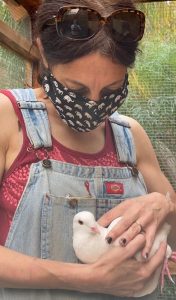

And so come home to roost were three snow-white pigeons. Lovely, petite Wheezy (the bravest of the bunch), recently hatched Minibix (squawky and a little full of himself), and big clumsy Coach Steve. No matter how fond one is of animals, or how studied or conscientious you are about animal welfare, adopting a critter (or three) seems to adjust perspective in a way that brings unique comfort and grinds up your insides all at once. Suddenly, you start seeing every living thing through the lens of how vulnerable they are. And how vividly individual.

This is how, what began as our pandemic project, turned into a passion. Each morning, I step briefly outside the crowded chaos of where I stay in Oakland to feed and water and clean the wooden structure that protects a trio of prehistoric beings. The stillness and dim light of the early hour, and the physicality of the tasks, connects me to something primal and profoundly satisfying. My birds flutter and coo with anticipation of breakfast and I chirp back with assurances of how good and sweet they are. Having a desk job feels contrived and far away, if fleetingly.

Who knows how these pigeons ended up at the Berkeley shelter in the first place, but their spindly legs wreathed in yellow and blue bands indicated they’d been born in captivity. Birds raised for squab, or for the purpose of being “released” (as proxy doves) at weddings or other events, can’t survive should they suddenly end up in the wild. With no ability to locate food or water, and immediate prey for a host of bigger birds, death is likely within days. Anyone who says they love pigeons and then races or breeds them has a wholly different definition of the emotion than I do.

Although having pigeons wasn’t what “turned me vegan” (that had happened years earlier), caring for them drives home a truth about animals that you sometimes take for granted with dogs and cats (and makes it harder to look away from the systemic animal cruelty that is … everywhere). The obvious devotion — and sheer affection — between Coach Steve and Wheezy was about as pure and uncomplicated as love gets. Pigeons mate for life, and in this case, it seemed life referred more to an attitude than to a span of time.

When Wheezy passed away, I thought Coach’s grief might kill me too. All cooing stopped. Flight itself practically ceased. He would simply stand in front of the mirror and stare, as if willing her to emerge from his reflection. Palomacy recommended allowing a few weeks for the widow to grieve and then to introduce a new female. Which is what we did. We chose one with a similar look to Wheezy (not sure that it mattered), and indeed Coach was resurrected. Those impenetrable black eyes again softened.

Mostly, the Big Shift of being newly responsible for caring for what was essentially a foreign species has been mental. It’s the awareness that humans are so much less exceptional than we tell ourselves. That so many others breathe and struggle and soar and weep, in whatever way that they do. A finch or scrub jay alighting on our patio table — and then just as quickly disappearing outside of frame — is more than a cameo in the plot-line of my life. This creature lives as full a day, each moment at a time, as any one of us. The vulnerability turns to strength, and then back again.

I can’t promise that this will be the last time I use the word “alighting” in a blog post, but I can tell you that I’m pretty confident my next piece will be back to focusing on animals of the hairy variety. Big blocky heads and magically fragrant paws are what I know best. Sometimes though, it’s just nice to spread your wings and see where you end up.

Leslie Smith is a writer at Best Friends Animal Society and the blog No Mushrooms. She’s passionate about pigeons, pig, pit bulls, and the otherwise misunderstood.

Leslie Smith is a writer at Best Friends Animal Society and the blog No Mushrooms. She’s passionate about pigeons, pig, pit bulls, and the otherwise misunderstood.