Guest Post & Photos by Zoe Martell

Zoe & Banano

As the bird health care coordinator for Palomacy, I often receive calls for help when something is awry with one of the many rescues in our volunteer network; this is how I first met Banano, a tame roller pigeon that had recently joined our network of rescued birds. Banano came into Palomacy’s care in October of 2015, when she was surrendered by the very loving woman who had cared for her for six years after finding her on the street. Banano was named by her rescuer’s son, then a toddler, who thought she resembled a banana and the name stuck. Banano was placed with a very loving Palomacy foster volunteer, Debbie, who quickly realized that something wasn’t right. Banano had arrived thin, wasn’t eating and was losing weight she didn’t have to spare. We figured the stress of moving might be part of it but I was asked to take her into my care to assess and support her.

Banano 10/13/15

Banano was thin and frail when I picked her up from Debbie. She’s a small bird and had dropped weight quickly after she stopped eating. I used my most sophisticated diagnostic tool – my nose – to examine some droppings, and was alerted to the likelihood of a bacterial infection. In addition to her droppings having a pungent smell, they were runny, and she was perching with her back hunched up. All of these signs pointed to a likely gastrointestinal or reproductive problem. I conferred with our director, Elizabeth, as to what our next steps should be. As a nonprofit agency, Palomacy is always stretched for funds, but we are dedicated to providing medical care to the birds that we rescue. Banano was so frail and depressed, however, we worried that she wouldn’t survive being hospitalized without some nurturing and stabilization first, so we made the decision to first treat with a broad-spectrum antibiotic and supportive care. (See River’s Flow to understand more about the impact of emotional support on a pigeon’s well being.)

I placed her on heat, and began tube feeding her and administering antibiotics and anti-inflammatory pain medication. Thankfully, she responded to this treatment, and began to gain weight and become stronger. She is a sweet, tame bird who greatly enjoys human contact. She is also very much a hen, and almost immediately she set her sights on winning over my partner, Chuck, as her new mate. She couldn’t get enough of his attention, wanting to cuddle with him every opportunity she had!

Banano loves Chuck!

After several days on antibiotics, she appeared much healthier, and began flying for the first time since coming into Palomacy’s care. As she perched on my hand, she passed a large mass that didn’t appear to be a normal dropping, after which she immediately seemed much less uncomfortable. I examined the mass, and discovered that it was many layers of thin membrane forming a ball that appeared to have a blood supply – I knew that this was most likely old egg material, and that there was likely more where that had come from. Her history revealed that she had laid eggs years before, but had stopped. I hoped for the best, but knew we’d likely need a vet visit in the near future. Occasionally, reproductive problems resolve with a single course of antibiotics, but often when a hen passes old egg material, it signals a larger problem. After passing the mass, Banano immediately stopped hunching her back, and began eating on her own. We agreed to watch and see what developed next. I exchanged messages with Lisa, the kind woman who had cared for Banano for 6 years, and learned that she had gone through periods of illness in the past, and had been treated with antibiotics before for similar behavior, though her vet had not reached a diagnosis for what was ailing her. After hearing this, I further suspected that we might be looking at something more complicated than a simple bacterial infection.

Zoe & Banano 11/20/15

Banano recovered over the next few weeks, gaining weight and strength, and doing her best to steal my partner away as her new mate. She cooed to him, she circled and dragged her tail, she flipped her little wing-tips alluringly. He often bowed to her in greeting as he walked by her cage, and she became frenzied with excitement whenever he entered the room.

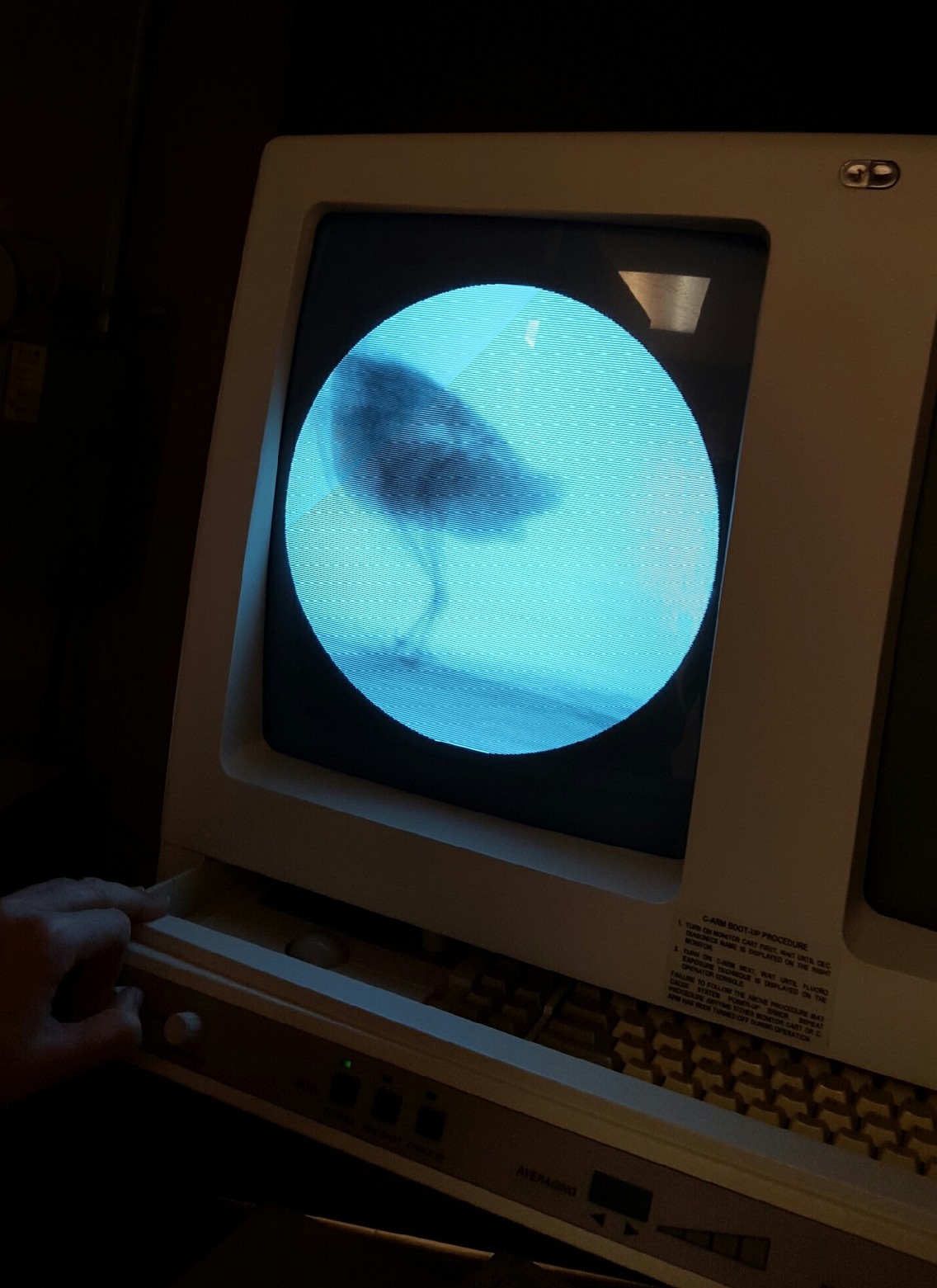

In January of 2016, I noticed that Banano was hunching up again, and that she was once again losing weight. It was time for a vet visit. We took Banano to the wonderful team at Medical Center for Birds. After an exam and radiological imaging, it was clear that there was a mass in Banano’s abdomen. Her intestinal tract was displaced to the side by something that appeared to be reproductive in nature. She was stable enough and had enough body fat that our veterinary team decided that she was a good candidate for surgery, and she was hospitalized in preparation. Fearing cancer, the veterinary team operated on her to remove the growth.

Palomacy volunteer Melne transported Banano to the vets

Diagnosing Banano

Banano weathered the surgery well, and we were all relieved that the mass in her oviduct did not appear to be cancer. Instead, she had a build-up of old egg material, and a cystic growth in her oviduct, as well as additional bacterial growth that antibiotics alone had not been able to target. Her entire oviduct was removed, and her abdominal cavity was cleaned out of infection and buildup. After post-surgical observation in the hospital, she was sent home with a full course of antibiotics and pain medication.

Banano recuperating on her heated bed

Now, we faced a new challenge, and it is one that is all too familiar to many of us; although she had nearly a full hysterectomy and her oviduct (egg gland) had been removed, Banano would still produce hormones, and she could potentially still ovulate. It is nearly impossible to remove the ovaries in pigeons, because they are adhered to the vena cava, which are large veins leading directly to the heart. If she ovulated, an egg yolk would form, which would need to be absorbed by the abdominal cavity. If something went wrong, egg material might build up in her abdomen and cause further problems. We consulted with our veterinarian Dr. Brenna Fitzgerald, who advised us to allow minimal touching and affection between Banano and her selected human mate, Chuck. In Dr. Fitzgerald’s words, Banano had now been relegated to the “friend zone.” I also consulted with another of our volunteers, who had a hen in a similar predicament. Friend zone it was, and I suspected Banano wouldn’t be happy about it.

I was right, and her first weeks back home were very difficult. Despite having just had major surgery, Banano was not deterred in her quest for love, and she did her best to coax Chuck away from me and into her little heated nest bed. She cooed, she dragged her tail, and she flicked her little wing tips frantically. Chuck remained the perfect gentleman, talking to her in a soothing manner, but gently handing her to me every time she put on the seduction routine. It was heartbreaking – Banano wanted his attention so badly, and he had grown so fond of her, it was nearly killing both of us to have him withhold the affection she so greatly craved. Tame pigeons love to snuggle, but petting and cuddling are often enough to stimulate the reproductive cycle. We allowed her to fly to his shoulder, and to land on his head, but he refrained from petting her, and refused to allow her to engage in mating behaviors such as sticking her beak between his fingers. She became frustrated at times, and would peck at me as viciously as a tiny roller pigeon can (I tried not to laugh,) attempting to come between me and Chuck, but we persisted in our efforts, knowing that her life could depend on it.

Chuck & Banano having a talk

Banano is now healed from surgery, and is greatly on the upswing. She has moved out of her small, single-room-occupancy dwelling into a large multi-story pigeon condo, and she has her own lighting source as well as bird neighbors and regular housecleaning and room service. She is housed alone, right next door to a very talkative starling, who provides company but not reproductive stimulation. She enjoys sitting on her perch and bowing to the starling, who makes a fantastic array of chittering sounds and wing gestures in return. Banano is allowed regular flight around our large bird room, and is allowed to visit Chuck so long as she stays in the friend zone. She has made peace with me, and enjoys riding around on my head or shoulder when I’m going about my business.

Banano is doing great

Banano will never be able to have a real mate, because it would be too dangerous to her health to allow it. Even a same-sex pigeon companion is out of the question, as pigeons, like people, often pair up with members of the same sex and mate. Our veterinary team determined that Banano was not a good candidate for Lupron shots or for the implants that suppress ovulation, so we will do our best to make her life happy and social while minimizing anything that could stimulate her reproductively. We love her dearly, and we want to be sure she has adequate social interaction, while still protecting her health. Thankfully, I think we have struck a good balance, and it also seems Banano’s hormones have also calmed down to a tolerable level. As Chuck remarked recently, “wow, Banano is acting just like a normal bird now!” Let’s hope that continues.

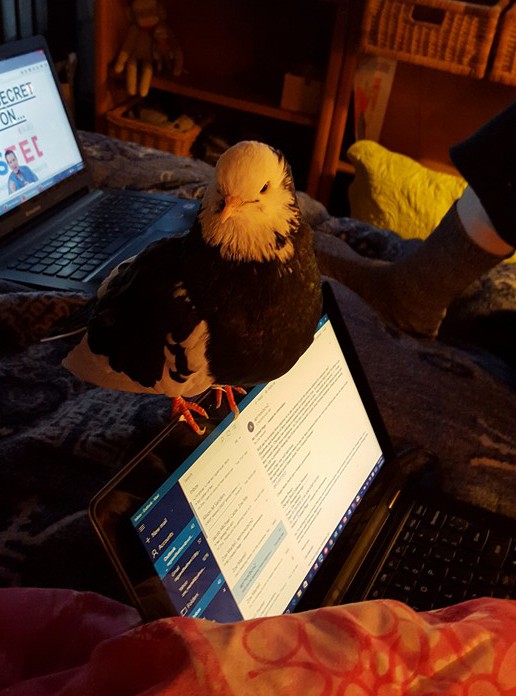

Banano helping with the editing

Note from Palomacy Director Elizabeth Young

We are all so grateful to Zoe for sharing her expert knowledge and care so generously in support of Palomacy birds (and so many others). Rescue work is always hard and Zoe takes on many of our most challenging cases. Without Zoe, Banano’s story would not have had a happy ending.

If you can, please support our rescue work with a donation.

To volunteer with us, please complete our online application.