In memoriam … written and photographed by Ingrid Taylar

————————————

First there was Blue. She came to us from the great blue, the wild blue, as blue as Lightin’ Slim, singing pigeon blues, not Rooster Blues.

She came on banded foot, born of two other Blues who gave our Blue her azul feathers and fuchsia feet … in a lineage that swept back through the blueness of her grandparents and past the great grandparents before them. They all commanded the skies and taught Blue, through genes and ingenuity, to carry on forward when the color of blue left her own skies.

She landed more than a decade after her wings first launched into flight, a decade after the first time she was jostled in a racing cage to places unknown, then sprung from the box to somehow find her own way home. A decade after all that, she landed hungry, tired, and lost — lost for whom or what we can never know. The only tie to her bloodline was etched in black and white around her ankle where the band scraped her aged skin. It revealed nothing more than a number no longer traceable to anyone or anything.

Blue arrived with maladies so we gave her medicine.

She slept by me while I wrote my papers, and watched me with the soulfulness of all who exist — viable and sentient.

And bathed in the sacred waters of her plastic tub.

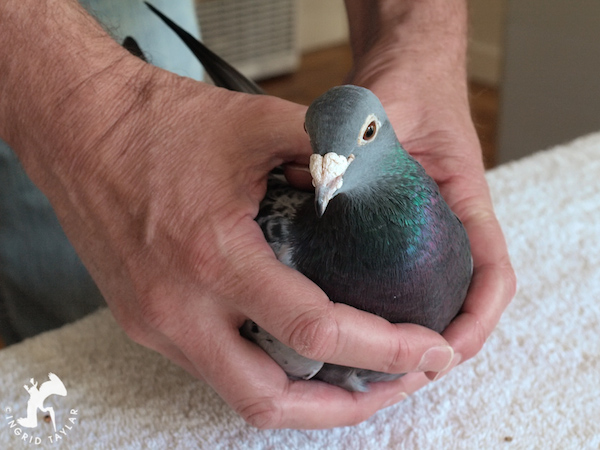

One day we decided to cut her free from her banded history once and for all. The vet said to Blue, “you are the most muscular bird I’ve ever held.” She was — incredibly muscular and strong as racers are bred to be. “We’re taking off these slave bracelets right now,” the vet added. Then with a gentle snap of her tools, she removed forever the human mandates from Blue’s avian life. We brought her home where for hours, she marched and lifted and preened her ankles. I knew, as well as any of us can know, that she felt just right again.

Blue could now be her blueness. But what does that mean for one of ancient blood, destined to flock and fly and be free, but now facing life alone and vulnerable and domesticated?

The answer came in the color White. White, a “he,” was as destitute as Blue had been and even more so. He was kept in a cage on wheels with a name tag that said “Snowflake” and with a bloody mess of a hawk hit on his breast. The shelter workers pushed Snowflake and his cage on that wheeled tray into the hallway when they disinfected his bird room and cleaned his wounds. And they put up a sign, hoping that someone who loved the Blues and Whites of the world would see it — that here was a Snowflake in need of home, heart and healing.

One of my friends, Elizabeth of MickaCoo, is just such a person and much, much more. She can almost hear the silent, cosmic cries of needy birds — and it was because of her that White found himself with our Blue.

In the sacred waters of her plastic tub.

And then, in the nest box we set up with fleeces, which White decorated on his own with tobacco twigs and coffee stir sticks we’d leave out for him to find.

In fact, White became a master builder of artistic dimensions with those stir sticks. Loyally, Blue sat on the pile of sticks no matter how high it grew, and I thought she was like the Princess and the Pea in reverse — that she could feel something soft and fleecy under the hard edges of White’s construction.

In rescue, it’s a sad thing for the birds and an often heartbreaking task for the caretakers, that the real eggs are replaced with wooden replicas to spare even more unwanted birds from being born. The birds sit on the wooden eggs with dedication and purpose, but those eggs never hatch.

When that day of recognition would come for Blue and White, I’d see Blue slough off the role of incubator, rise up from her month-long sit, stretch her wings and then resume the routine all over again when next eggs came around.

In the nesting box below, White also included a clothespin, some hay stems, and a plastic tie wrap he found somewhere. You can see how pigeons get themselves in trouble and entangled around the ankles when you watch them scout for nesting materials.

Blue and White were now bonded in cycles that only pigeons can know. They became inseparable … except for those times when White preferred his own reflection to Blue’s elegant allure. We forgave White his moments as Narcissus, seeing as how he was a youthful one year to Blue’s saucy ten.

Blue was no longer attentive to my deadlines. She had eyes only for White and he for her. When I say inseparable, I mean a shadow and reflection, a George and a Gracie … a Blue and a White in perfect symbiosis and contrast.

We finally mustered the resolve to take White in to have his double bands removed as well. We’d put it off because neither Blue nor White relished the carrier nor the car nor the vet, but we couldn’t stand to see him pick at the bracelets he couldn’t remove on his own. White’s bands didn’t snap off as easily as Blue’s did. One was plastic fused to metal and pressed so tightly to his skin that removal was hazardous to his leg.

But once again, our vet, with extra care, freed this bird from the sentence he no longer had to serve.

And White, too, just like Blue, spent the hours late into evening, marching, lifting and preening those ankles — skin now feeling a gentle beak and fresh air for the first time since White was banded as a baby.

White, in all of his shimmering whiteness, had poses for the ages …

He just couldn’t look anything but starry and dreamy.

So, it’s fitting that White found himself the centerpiece of a German record album …

And on fund-raising t-shirts for MickaCoo Pigeon and Dove Rescue …

Blue and White moved to a bountiful flight aviary in Northern California, with grape vines growing inside in which Diamond doves nested. It was decked with swinging branches to perch on, baths made of stone and 50 pound bags of feed. The two of them shared this world with a few rescued King Pigeons and ducks, and they remained inseparable, just as they’d been, until the day this past year when Blue became ill. We hoped to heal her but it was cancer gone horribly aggressive. So, with the help of a vet, Blue fell into her last sleep under the care of the person who gave her that aviary paradise, the warm Delta winds, California sunshine and grape vines.

I cried many days after I first dropped Blue and White at their new aviary home, the loss felt immense. And, those tears gushed again when Blue died — that transcendent little spirit in feathered azul.

What I didn’t know until after the fact was that Blue managed to leave behind a little Blue-and-White surprise. Two little Blue-and-White surprises, actually.

Our bonded duo had cleverly stashed their eggs behind a food bin so as to avoid detection. Then, when a substitute caretaker was in the house, a caretaker who didn’t know all of their Blue and White secrets, they managed to incubate those eggs to hatching. And as a consequence, they bred two healthy babies made of Blue … and made of White.

Now White and the two younger Blue-and-Whites share the aviary with the King Pigeons, the Diamond doves, and two ducks. I saw them for the first time in October when I was in California. Before I post their photo, I will show you what White was doing as I tried to approach him. In sum I felt him say: “Stay away from me, Lady! I got it good here!”

There was recognition — but simultaneous trepidation. He didn’t know what it meant that I was there and he didn’t want to find out. This was one of the only in-focus shots I snapped of him as he raced out of arm’s reach and back to shelter.

Lazing on a swinging perch was one of White’s progeny, gazing at me with the look of the ancients … carried down from the parents of Blue and her grandparents, and the parents of White and his grandparents. Little Blue-and-White was a blend of Blue and White so perfect as to be a living continuity of her mother.

Later, inside the nesting shed, I found the two of Blue’s babies together … taut and muscular like their dear old mum, with the spirited eye of their dad.

I suspect that like many first-generation kids of true survivors, these two can’t fully grasp what an arduous road it was for Blue and White, from their breeding boxes, and forced separations, the hundred-mile flights and raptor injuries, until finally blown off course into the unknown. But, I’m sure they carry with them some innate spark of genes and ingenuity that Blue and White were handed themselves, a spark that connects them always to the birds they are — through the generations of birds they never knew.

I thank Blue (our dear sweet late Chauncey) … and White (our beloved Clive) … with all of my heart … for connecting the two of us in a most poignant and unforgettable way to this existence outside our own. We will be forever cognizant, careful and compassionate about the lives of birds in their individual greatness, and in their shared magic as citizens of the grand and spectacular avian nation.